A Journey Through Statistical Mechanics

"When we gaze at a glass of still water, we see the 'tranquility' and 'certainty' of the macroscopic world. Yet, at the microscopic level, a chaotic storm involving

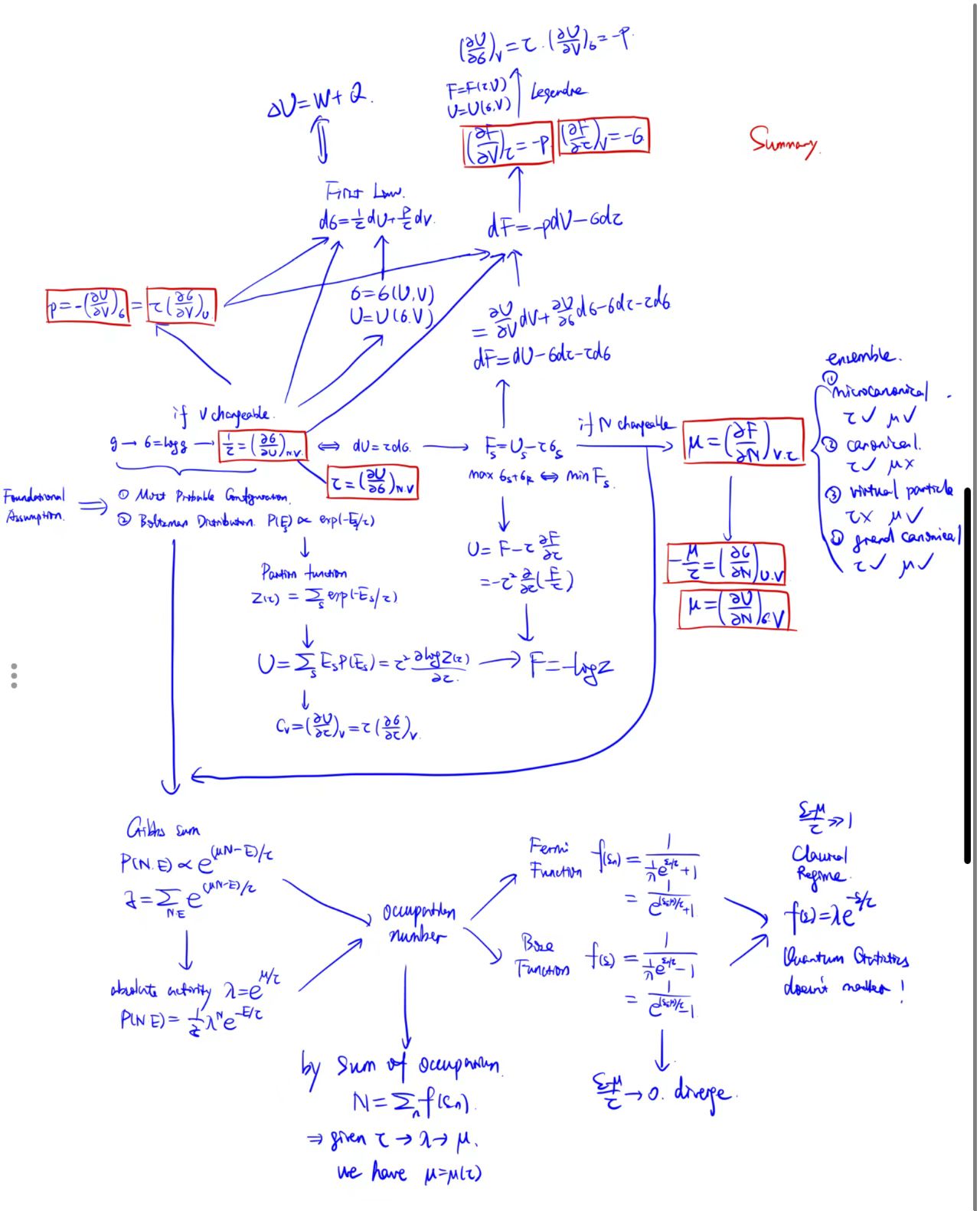

Among the many branches of physics, statistical mechanics possesses a unique logical beauty. It requires neither the intricate force analysis of classical mechanics nor the complex interaction terms of quantum field theory. It requires only one extremely simple axiom—the 'Fundamental Assumption of Statistical Mechanics.' As long as you acknowledge that in an isolated system, every possible microstate appears with equal probability, the rest of the thermodynamic universe—from the definition of temperature to the Boltzmann distribution, from the derivation of chemical potential to Bose-Einstein condensation—can be deduced as naturally as falling dominoes.

This is a story about 'More is Different.' This article aims to strip away complex specific models and restore the original skeleton of thermal physics. We will start from the Multiplicity Function and, guided by Entropy, retrace the marvelous journey from microscopic counting to macroscopic prediction."

This is a story about 'More is Different.' This article aims to strip away complex specific models and restore the original skeleton of thermal physics. We will start from the Multiplicity Function and, guided by Entropy, retrace the marvelous journey from microscopic counting to macroscopic prediction."

Note: This article assumes the reader possesses basic knowledge and concepts of quantum mechanics, as statistical mechanics is inherently quantum in nature. We are, in effect, calculating the statistical effects of massive quantities of quanta.

Chapter 1: The Art of Counting — From Multiplicity to Thermal Equilibrium

Our journey begins with a question so simple it seems outrageous: Under given macroscopic conditions, how many possible microscopic 'ways of living' does a system have?

Physicists have given this number of 'ways' a name: Multiplicity, usually denoted by the symbol

1. The Fundamental Assumption: Nature is Fair

Imagine an isolated box containing

Statistical mechanics is built upon a single, foundational axiom—the Fundamental Assumption:

For an isolated system, all accessible quantum states that satisfy energy conservation appear with equal probability.

This means Nature plays no favorites. As long as the energy allows it, the chance of the system being in state A is exactly the same as being in state B.

2. Why Define Entropy? (

If multiplicity

This is not for mystification, but for two extremely pragmatic reasons:

-

The numbers are too large:

For macroscopic objects,is an astronomical figure. Even for a small vial of gas, the order of magnitude of might be . Handling such numbers is not only troublesome but mathematically unintuitive. -

We need Additivity:

Imagine you have two glasses of water, System A and System B.- If you view them as a whole, the total number of states is the product of their individual states:

(combinatorial principle). - However, in macroscopic physics, we are used to "addition." Mass adds up, volume adds up, energy adds up. We want this quantity describing the "degree of disorder" to be additive as well.

- If you view them as a whole, the total number of states is the product of their individual states:

What mathematical tool turns multiplication into addition while taming massive exponents into manageable numbers? The answer is the logarithm.

Thus, Boltzmann (and Planck) provided one of the most profound definitions in physics—Fundamental Entropy:

Entropy, in essence, is the logarithm of the number of microstates. It is not some mysterious destructive force; it is simply our measure of a system's "possibility."

3. Why Does Thermal Equilibrium Mean Maximum Entropy?

Now, let us witness the moment of magic.

Suppose we place two independent systems, A and B, together and allow them to make Thermal Contact. This means they can exchange energy, but the total energy

How will the system evolve?

According to the Fundamental Assumption, the system will random walk, trying various energy distributions. However, there is one distribution whose probability will overwhelmingly dominate all others—the one that maximizes the total number of microstates

Mathematically, maximizing

Using only the single basic assumption of statistical mechanics, the multiplicity of the entire system is

Now, if we consider that only the most probable configuration contributes to

Conclusion: The system evolves toward thermal equilibrium because that equilibrium state possesses the greatest number of microstates. Entropy increase is, fundamentally, the system evolving in the direction of "more possibilities."

4. The Birth of Temperature: Why Define it as a Derivative?

When two systems reach thermal equilibrium (maximum entropy), what happens? According to calculus, when a function reaches an extremum, its derivative is zero.

We differentiate the total entropy with respect to the energy distribution:

Since energy is conserved (

Substituting this back, we obtain the critically important equilibrium condition:

Pause to reflect:

When two objects reach thermal equilibrium, what physical quantity is equal? Intuition tells us it is Temperature.

This implies that the mathematical quantity

Let's look at the physical meaning of this quantity: it is the "rate of change of entropy with respect to energy."

- When you give a cold object a little energy, its disorder (number of states) increases drastically. A cold object is "hungry" for energy (

is large). - When you give a hot object a little energy, the increase in its disorder is negligible. A hot object is "indifferent" to energy (

is small).

Since a larger

Therefore, to align with human cognitive habits, we define the fundamental temperature (

This is the rigorous definition of temperature in statistical mechanics: Temperature measures the system's willingness to "pay" energy in exchange for increased entropy.

- Low Temperature means a huge entropy gain for a tiny energy cost (high cost-performance ratio).

- High Temperature means even a large energy input yields minimal entropy increase.

If examined closely, one finds that the definition of temperature shares the same form as half-life; just as half-life shares dimensions with time, temperature shares dimensions with energy (in natural units).

Chapter 2: The Birth of Pressure

1. Why is Entropy a Function of

First, we must answer a meta-question: Why do we always write entropy as

This is because, at the microscopic level, Multiplicity (

(Energy): Determines the "budget" you can allocate for particle motion. (Volume): Determines the "space" available for particles to occupy (in quantum mechanics, volume determines the wavelength of standing waves, i.e., the energy level structure). (Particle Number): Determines how many "actors" are participating in this chaotic performance.

Since

Previously, we only took the partial derivative with respect to

2. Pressure: The Craving for Spatial Expansion

Imagine replacing our rigid container with a cylinder equipped with a piston. Now, the volume

When volume changes, quantum mechanics tells us that energy levels actually shift:

- Considering statistical mechanics, we calculate the statistical average:

. Since , we have . - From another angle, the change in energy is the work done by pressure:

. - Thus, we obtain

. The negative sign exists because pressure doing positive work causes volume to decrease.

There is another non-trivial way to write Pressure:

Essentially, pressure represents the intensity of the "desire to expand volume to increase entropy." After all, when volume increases slightly (

Chapter 3: A Shift in Perspective — Why Introduce Free Energy?

We already have entropy

It is very difficult to control the total energy

Imagine boiling a cup of water in a lab. It is easy to control temperature (using a constant-temperature hot plate) and volume (using a rigid cup), but it is incredibly hard to precisely control how many Joules of internal energy are in that water, as heat flows in and out constantly.

When we switch from an "isolated system" (fixed

We need a new guiding light—a quantity that tends toward an extremum under fixed temperature

1. Helmholtz Free Energy

Suppose two systems are in thermal contact. One is a massive Heat Reservoir, and the other is the System of interest (fixed

Defining

- Since temperatures are equal at equilibrium,

, so , leading to . This is why we define this way—to find an extremum. Recall that for a system and a reservoir, the equilibrium condition is maximizing . We don't actually care about the reservoir, and minimizing system Free Energy gives us a way to ignore the reservoir while still determining equilibrium. Let's prove it is a minimum. - Total entropy is

. Since the reservoir is huge, we Taylor expand: . Clearly, maximizing entropy is equivalent to minimizing Free Energy. Note that entropy belongs to the system plus reservoir, but free energy belongs only to the system. . This is a beautiful result. With free energy, we can disregard the reservoir. The reservoir contributes only a , which is a fixed constant at equilibrium.

2. Chemical Potential: The Driving Force of Particle Flow

Now we release the final variable: particle number

- Crucially,

. - Recalling that free energy

must be minimized ( ), we have , implying .

We introduce the Weak Link Assumption: Assume the tube is thin enough that the two systems are statistically independent (so

- Thus,

. This is the equilibrium condition. - From this, we define chemical potential:

.

You might ask if a single system needs a chemical potential, since the definition seems to require two. In fact, we can draw an analogy with temperature:

- An isolated closed system needs neither

nor . This is the microcanonical ensemble. - If this system contacts a heat reservoir, we need

but not to describe it. This is the canonical ensemble (most common in traditional thermal physics). - If this system contacts a particle reservoir, we don't need

but need . While such systems exist (where particles are "virtual," carrying no energy, like information), they are rare in standard material physics. - If the system contacts both a heat and particle reservoir, we need both

and . This is the grand canonical ensemble.

Previously, the definition of pressure was derived from energy

Using the first, we directly get

Using the second, we get

Chemical potential describes the system's willingness to "accept new particles to increase entropy." The physical intuition is that matter tends to flow from high to low (water flows down, charge flows to low potential). Here, particles naturally flow from High Chemical Potential to Low Chemical Potential (to maximize total entropy). Without the negative sign, particles would counter-intuitively flow from low to high.

Chapter 4: Thermodynamic Identities — Different Faces of the Same Truth

We have defined entropy, temperature, pressure, and chemical potential. Now, we enter the interior of the edifice to explore the intricate yet symmetrical relationships between these quantities. Through the art of differentiation, we will reveal the essence of the First Law of Thermodynamics and show how to navigate different "energy landscapes" via mathematical transformations. You will find that thermal physics, unlike classical mechanics with its single core law (

1. Three Ways to Write the First Law

Let's play a differential game to see what results from starting with different functions.

Perspective 1: Entropy

If we view entropy as a function of internal energy and volume, its total differential is:

Recall our definitions:

Multiplying by

Or the familiar form:

Here

Conclusion: The First Law of Thermodynamics (Energy Conservation) is mathematically equivalent to the fact that "entropy is a function of state variables

Perspective 2: Internal Energy

If we flip the perspective and view internal energy as a function of entropy and volume:

This is still the First Law, but the viewpoint has shifted: Temperature is the slope of internal energy vs. entropy, and Pressure is the slope of internal energy vs. volume.

Perspective 3: Free Energy

This is the most brilliant step. Recall

Substituting

The term

This means if we view

2. The Core Truth:

Faced with so many formulas, you might ask: What is the core of thermal physics? Is there a governing formula like

The answer is yes. The soul of thermal physics is

Let's prove this with a thought experiment. Consider two systems

- Energy Exchange:

- Volume Exchange (Movable partition):

- Particle Exchange (Perforated partition):

When does the system reach equilibrium? When total entropy is maximized, i.e.,

Approximating

Expanding the differentials:

Using conservation relations

Since

- Energy Equilibrium:

(Equal Temperature) - Volume Equilibrium:

- Particle Equilibrium:

Key Insight: Strictly speaking, the conditions for equilibrium are the equality of

and . It is only because we typically also exchange energy (making equal) that we get the familiar and . All thermodynamic quantities essentially emerge from the extremum condition .

3. Conjugate Variables — Dancing Partners

If we look back at internal energy

The independent variables

Physicists define Generalized Force:

This reveals that physical quantities appear in pairs, each containing one extensive and one intensive quantity, known as Conjugate Variables:

| Extensive Variable | Intensive Variable / Generalized Force | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Entropy |

Temperature |

|

| Volume |

Pressure |

|

| Particle Number |

Chemical Potential |

This offers a new perspective to understand thermal physics via classical mechanics (force balance): Thermal equilibrium is essentially the static equilibrium of generalized forces.

4. Legendre Transformation — Changing the Subject

Finally, we explain mathematically why the construction

In experiments, controlling entropy

Consider a function

(Note: here

Differentiation gives:

Since

This is the magic of Duality: it changes the independent variable from

This holds for multivariate functions

(New) (Unchanged) (Unchanged)

We have now derived all thermodynamic relations and understood why Free Energy acts as a potential function tailored for a reality where "temperature is easier to control than entropy."

Chapter 5: The Rosetta Stone of Thermal Physics

After four chapters, we have examined the system from three angles: Microscopic Counting (Entropy), Energy Conservation (Internal Energy), and Pragmatism (Free Energy). It seems like the blind men and the elephant—different parts, different descriptions. If we align the three potentials

| Quantity | Entropy Representation σ(U,V,N) | Internal Energy Representation U(σ,V,N) | Free Energy Representation F(τ,V,N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temp |

|||

| Pressure |

|||

| Chem Pot |

We must interpret three layers of information from this table.

1. The "Definitions" on the Diagonal

While every equation is mathematically valid, physicists typically use the diagonal from top-left to bottom-right to establish definitions:

- Row 1, Col 1:

. The Statistical Mechanics Definition of temperature. - Row 2, Col 2:

. The Mechanical Definition of pressure (Generalized Force). - Row 3, Col 3:

. The Practical Definition of chemical potential (change in free energy when adding a particle at constant ).

2. "The One Truth" and Redundancy

Do you need to memorize all 9 formulas? No.

The last two columns are technically "redundant." The entire physics is contained in the first column (Entropy).

- Once you have

, you have the universe. - Column 2 (

) is just an inverse function. - Column 3 (

) is just a Legendre transform.

Physicists keep them not for new information, but for coordinate convenience (it is easier to hold

3. Mathematical Bridges

How do you derive Column 2 from Column 1? It's just calculus.

Bridge 1: Reciprocal Relation

Comparing Row 1:

This uses the Inverse Function Rule:

Bridge 2: Cyclic Relation

Comparing Row 3:

Why the strange

Letting

Substituting definitions from Column 2 (numerator is

Chapter 6: The Great Reversal — From Partition Functions to Gibbs Sums

We spent chapters building thermodynamics from microscopic counting (

- Concept:

. - Computation:

is usually despairingly hard to calculate (imagine counting permutations of particles).

So, physicists invented a "Reverse Channel": Write the energy model, calculate the Partition Function (

We introduce two superstars: Boltzmann Distribution (fixed

1. Boltzmann Distribution

Consider System

Since we specify a precise microstate of

The probability ratio equals the ratio of the Reservoir's multiplicities:

Using

Information Entropy Perspective:

If we seek the "most unbiased" probability distribution (maximizing Shannon Entropy

) given only the average energy , Lagrange multipliers similarly yield . The Boltzmann distribution is Nature's most "natural," unbiased choice.

2. The Partition Function: The Holy Grail

To normalize

So

Why is it the "Holy Grail"?

Using

The Computational U-Turn:

- List Microscopic Model (Energy levels

). - Sum to find

(Geometric series or Gaussian integral). - Find

( ). - Find Everything (

, , , via derivatives of ).

3. Gibbs Sum: When Particles Flow

If the system exchanges particles too (Grand Canonical), the Reservoir's entropy

Taylor expansion adds a term:

This gives the Gibbs Distribution:

The normalization constant is the Grand Partition Function or Gibbs Sum (

Defining Absolute Activity

A Paradox? In Boltzmann,

Chapter 7: Quantum Statistics — When Particles Lose Their Names

Finally, we address the elephant in the room—Quantum Mechanics. Previously, we treated particles as distinguishable "balls." Now, we face the reality of Indistinguishability.

1. Who is it? No, What is it?

In the quantum world, identical particles are fundamentally indistinguishable. Exchanging two particles leaves the probability density

This

- Bosons (+1): Social, like to cluster (Photons, Helium-4).

- Fermions (-1): Anti-social, follow Pauli Exclusion, never occupy the same state (Electrons, Protons).

Counting Changes:

Putting 2 particles in 4 energy levels:

- Classical:

ways. - Bosons: 10 ways (Enhanced probability of being together).

- Fermions: 6 ways (Zero probability of being together).

Sincechanges, Entropy and macro-properties change.

2. From Particle View to Orbital View

Instead of asking "Where is Particle A?", we ask "How many particles are in Energy Level

Since the number of particles in a level can vary, we use the Gibbs Sum.

3. Fermi-Dirac and Bose-Einstein Distributions

Fermions:

Occupancy

Average occupancy:

The

Bosons:

Occupancy

Average occupancy:

The

4. Classical Limit: All Roads Lead to Rome

Why don't we feel this difference daily? Because we live in the Classical Regime: High temperature or low density (

The

This is the Boltzmann Distribution!

However, when we cool down past the Quantum Concentration (

Conclusion: Order Emerging from Ignorance

Our journey ends here. Let us look back at the structure we built.

- We started with an admission of "ignorance": the Principle of Equal Probability.

- We quantified "possibility" via Counting and Entropy.

- By maximizing entropy, we discovered macroscopic islands of Temperature, Pressure, and Chemical Potential emerging from the chaotic microscopic sea.

- We navigated via Free Energy and used Partition Functions as our compass.

- Finally, injecting Quantum nature, the framework predicted states of matter under extreme conditions.

Notably, we barely mentioned specific substances. We didn't calculate the specific heat of copper or the rotation of oxygen. That is the charm of statistical mechanics: It is a universal grammar, not a specific story.

It describes the logic of "Many," not the identity of "One." Whether it's molecules in a gas, photons in a cavity, or nuclear matter in a star, as long as you input the Hamiltonian, the macro-properties emerge automatically.

What is Thermal Physics?

It is the science of "More." It is about how, when countless tiny individuals gather, a new, deterministic macroscopic order emerges through statistical laws—an order not possessed by the individuals themselves.

This is perhaps the deepest poetry in physics: God does not need to play dice; chaos itself is the source of order.